KAMUELA, Hawaii (February 15th, 2004) A team of astronomers may have discovered the most distant galaxy in the universe. Located an estimated 13 billion light-years away, the object is being viewed at a time only 750 million years after the big bang, when the universe was barely 5 percent of its current age.

The primeval galaxy was identified by combining the power of NASAs Hubble Space Telescope and CARA’s W. M. Keck Telescopes on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. These great observatories got a boost from the added magnification of a natural cosmic gravitational lens in space that further amplifies the brightness of the distant object.

We are looking at the first evidence of our ancestors on the evolutionary tree of the entire universe,” said Dr. Frederic Chaffee, director of the W. M. Keck Observatory, home to the twin 10-meter Keck telescopes that confirmed the discovery. “Telescopes are virtual time machines, allowing our astronomers to look back to the early history of the cosmos, and these marvelous observations are of the earliest time yet.”

The newly discovered galaxy is likely to be a young galaxy shining during the end of the so-called “Dark Ages”—the period in cosmic history which ended with the first galaxies and quasars transforming opaque, molecular hydrogen into the transparent, ionized universe we see today.

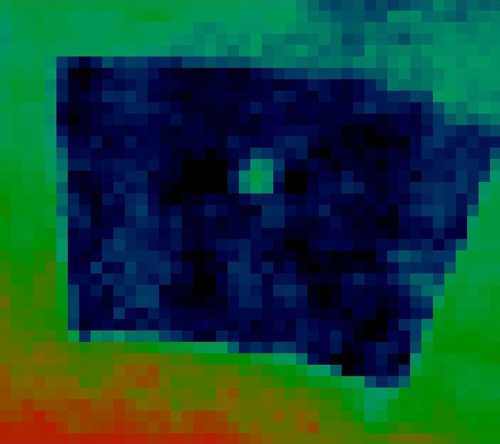

The new galaxy was detected in a long exposure of the nearby cluster of galaxies Abell 2218, taken with the Advanced Camera for Surveys on board the Hubble Space Telescope. This cluster is so massive that the light of distant objects passing through the cluster actually bends and is amplified, much as a magnifying glass bends and magnifies objects seen through it. Such natural gravitational “telescopes” allow astronomers to see extremely distant and faint objects that could otherwise not be seen. The extremely faint galaxy is so far away its visible light has been stretched into infrared wavelengths, making the observations particularly difficult.

“As we were searching for distant galaxies magnified by Abell 2218, we detected a pair of strikingly similar images whose arrangement and color indicate a very distant object,” said California Institute of Technology (Caltech) astronomer Jean-Paul Kneib, who is lead author reporting the discovery in a forthcoming article in the Astrophysical Journal.

Analysis of a sequence of Hubble images indicate the object lies in between a redshift of 6.6 and 7.1, making it the most distant source currently known. However, long exposures in the optical and infrared taken with spectrographs on the 10-meter Keck telescopes suggests that the object has a redshift towards the upper end of this range, around redshift 7.

Redshift is a measure of how much the wavelengths of light are shifted to longer wavelengths. The greater the shift in wavelength toward the redder regions of the spectrum, the more distant the object is.

“The galaxy we have discovered is extremely faint, and verifying its distance has been an extraordinarily challenging adventure,” said Dr. Kneib. “Without the magnification of 25 afforded by the foreground cluster, this early object could simply not have been identified or studied in any detail at all with the present telescopes available. Even with aid of the cosmic lens, the discovery has only been possible by pushing our current observatories to the limits of their capabilities!”

Using the combination of the high resolution of Hubble and the large magnification of the cosmic lens, the astronomers estimate that this object, although very small—only 2,000 light-years across—is forming stars extremely actively. However, two intriguing properties of the new source are the apparent lack of the typically bright hydrogen emission line and its intense ultraviolet light which is much stronger than that seen in star-forming galaxies closer by.

“The properties of this distant source are very exciting because, if verified by further study, they could represent the hallmark of a truly young stellar system, that ended the Dark Ages,” added Dr. Richard Ellis, Steele Professor of Astronomy at Caltech, and a co-author in the article.

The team is encouraged by the success of their technique and plans to continue the search for more examples by looking through other cosmic lenses in the sky.

“Estimating the abundance and characteristic properties of sources at early times is particularly important in understanding how the universe reionized itself, thus ending the Dark Ages,” said Mike Santos, a former Caltech graduate student, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, UK. “The cosmic lens has given us a first glimpse into this important epoch. We are now eager to learn more by finding further examples, although it will no doubt be challenging.”

The Caltech team reporting on the discovery consists of Drs. Jean-Paul Kneib, Richard S. Ellis, Michael R. Santos and Johan Richard. Drs. Kneib and Richard also serve the Observatoire Midi-Pyrenees of Toulouse, France. Dr. Santos also represents the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, UK.

The W.M. Keck Observatory is operated by the California Association for Research in Astronomy, a scientific partnership of the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.