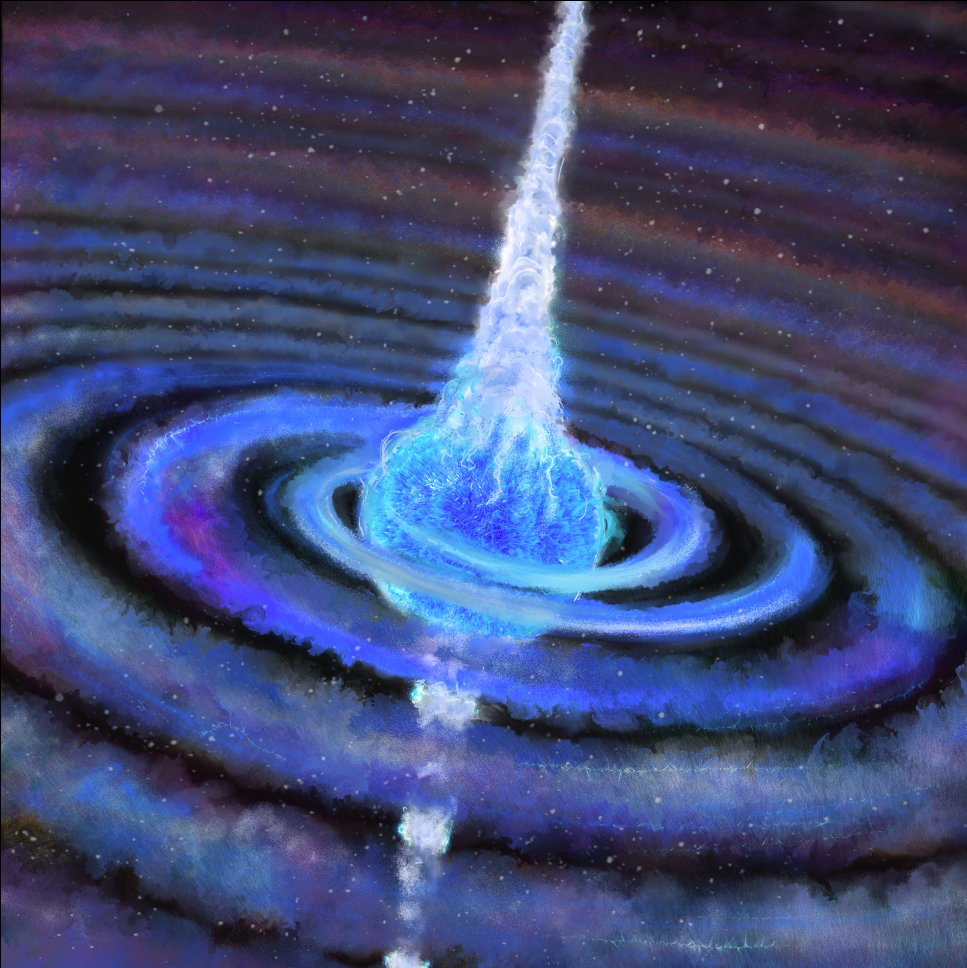

The first observation of a brand-new kind of supernova had been predicted by theorists but never before confirmed

Maunakea, Hawaiʻi – In 2017, a particularly luminous and unusual source of radio waves was discovered in data taken by the Very Large Array (VLA) Sky Survey, a project that scans the night sky in radio wavelengths. Now, led by Caltech graduate student Dillon Dong, a team of astronomers has established that the bright radio flare was caused by a black hole or neutron star crashing into its companion star in a never-before-seen process.

“Massive stars usually explode as supernovae when they run out of nuclear fuel,” says Gregg Hallinan, professor of astronomy at Caltech. “But in this case, an invading black hole or neutron star has prematurely triggered its companion star to explode.” This is the first time a merger-triggered supernova has ever been confirmed.

A paper about the findings, which includes data from W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea in Hawaiʻi, appears in the journal Science on September 3.

Two Unusual Events

Following Dong’s discovery, Caltech graduate student Anna Ho (PhD ’20) suggested that this radio transient be compared with a different catalog of brief bright events in the X-ray spectrum. Some of these X-ray events were so short-lived that they were only present in the sky for a few seconds of Earth time. By examining this other catalog, Dong discovered a source of X-rays that originated from the same spot in the sky as VT 1210+4956. Through careful analysis, Dong established that the X-rays and the radio waves were likely coming from the same event.

“The X-ray transient was an unusual event—it signaled that a relativistic jet was launched at the time of the explosion,” says Dong. “And the luminous radio glow indicated that the material from that explosion later crashed into a massive torus of dense gas that had been ejected from the star centuries earlier. These two events have never been associated with each other, and on their own they’re very rare.”

A Mystery Solved

So, what happened? After careful modeling, the team determined the most likely explanation—an event that involved some of the same cosmic players that are known to generate gravitational waves.

They speculated that a leftover compact remnant of a star that had previously exploded—that is, a black hole or a neutron star—had been closely orbiting around a star. Over time, the black hole had begun siphoning away the atmosphere of its companion star and ejecting it into space, forming the torus of gas. This process dragged the two objects ever closer until the black hole plunged into the star, causing the star to collapse and explode as a supernova.

The X-rays were produced by a jet launched from the core of the star at the moment of its collapse. The radio waves, by contrast, were produced years later as the exploding star reached the torus of gas that had been ejected by the inspiraling compact object.

Astronomers know that a massive star and a companion compact object can form what is called a stable orbit, in which the two bodies gradually spiral closer and closer over an extremely long period of time. This process forms a binary system that is stable for millions to billions of years but that will eventually collide and emit the kind of gravitational waves that were discovered by LIGO in 2015 and 2017.

However, in the case of VT 1210+4956, the two objects instead collided immediately and catastrophically, producing the blasts of X-rays and radio waves observed. Although collisions such as this have been predicted theoretically, VT 1210+4956 provides the first concrete evidence that it happens.

Serendipitous Surveying

The VLA Sky Survey produces enormous amounts of data about radio signals from the night sky, but sifting through that data to discover a bright and interesting event such as VT 1210+4956 is like finding a needle in a haystack. Finding this particular needle, Dong says, was, in a way, serendipitous.

“We had ideas of what we might find in the VLA survey, but we were open to the possibility of finding things we didn’t expect,” explains Dong. “We created the conditions to discover something interesting by conducting loosely constrained, open-minded searches of large data sets and then taking into account all of the contextual clues we could assemble about the objects that we found. During this process you find yourself pulled in different directions by different explanations, and you simply let nature tell you what’s out there.”

ABOUT LRIS

The Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS) is a very versatile and ultra-sensitive visible-wavelength imager and spectrograph built at the California Institute of Technology by a team led by Prof. Bev Oke and Prof. Judy Cohen and commissioned in 1993. Since then it has seen two major upgrades to further enhance its capabilities: the addition of a second, blue arm optimized for shorter wavelengths of light and the installation of detectors that are much more sensitive at the longest (red) wavelengths. Each arm is optimized for the wavelengths it covers. This large range of wavelength coverage, combined with the instrument’s high sensitivity, allows the study of everything from comets (which have interesting features in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum), to the blue light from star formation, to the red light of very distant objects. LRIS also records the spectra of up to 50 objects simultaneously, especially useful for studies of clusters of galaxies in the most distant reaches, and earliest times, of the universe. LRIS was used in observing distant supernovae by astronomers who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011 for research determining that the universe was speeding up in its expansion.

ABOUT W. M. KECK OBSERVATORY

The W. M. Keck Observatory telescopes are among the most scientifically productive on Earth. The two 10-meter optical/infrared telescopes atop Maunakea on the Island of Hawaii feature a suite of advanced instruments including imagers, multi-object spectrographs, high-resolution spectrographs, integral-field spectrometers, and world-leading laser guide star adaptive optics systems. Some of the data presented herein were obtained at Keck Observatory, which is a private 501(c) 3 non-profit organization operated as a scientific partnership among the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The Observatory was made possible by the generous financial support of the W. M. Keck Foundation. The authors wish to recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that the summit of Maunakea has always had within the Native Hawaiian community. We are most fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct observations from this mountain.