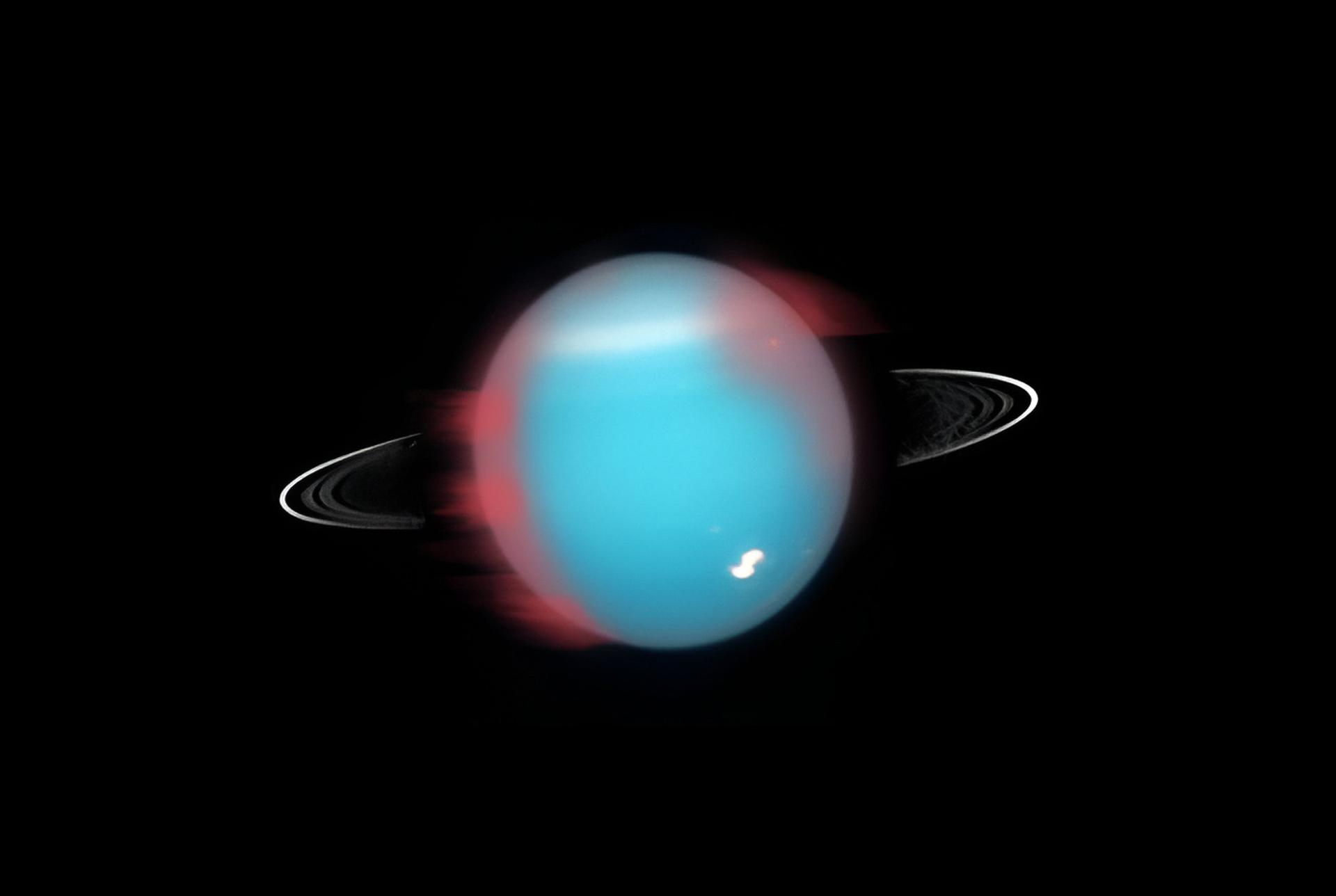

Maunakea, Hawaiʻi – The presence of an infrared aurora on the cold, outer planet of Uranus has been confirmed for the first time by University of Leicester astronomers.

The discovery could shed light on the mysteries behind the magnetic fields of the planets of our solar system, and even on whether distant worlds might support life.

Using W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea, Hawaiʻi Island, the team of scientists, supported by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), have obtained the first measurements of the infrared aurora at Uranus since investigations began in 1992. While the ultraviolet aurorae of Uranus has been observed since 1986, no confirmation of the infrared aurora had been observed until now. The scientists’ conclusions are published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The ice giants Uranus and Neptune are unusual planets in our solar system as their magnetic fields are misaligned with the axes in which they spin. While scientists have yet to find an explanation for this, clues may lie in Uranus’s aurora.

Aurorae are caused by highly energetic charged particles, which are funneled down and collide with a planet’s atmosphere via the planet’s magnetic field lines. On Earth, the most famous result of this process are the spectacles of the Northern and Southern Lights. At planets such as Uranus, where the atmosphere is predominately a mix of hydrogen and helium, this aurora will emit light outside of the visible spectrum and in wavelengths such as the infrared.

The team used infrared auroral measurements taken by analyzing specific wavelengths of light emitted from the planet, using the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSPEC) on the Keck II telescope. From this, they can analyze the light (known as emission lines) from these planets, similar to a barcode. In the infrared spectrum, the lines emitted by a charged particle known as H3+ will vary in brightness depending on how hot or cold the particle is and how dense this layer of the atmosphere is. Hence, the lines act like a thermometer into the planet.

Their observations revealed distinct increases in H3+ density in Uranus’s atmosphere with little change in temperature, consistent with ionization caused by the presence of an infrared aurora. Not only does this help us better understand the magnetic fields of the outer planets of our own solar system, but it may also help in identifying other planets that are suitable of supporting life.

“The temperature of all the gas giant planets, including Uranus, are hundreds of degrees Kelvin/Celsius above what models predict if only warmed by the Sun, leaving us with the big question of how these planets are so much hotter than expected? One theory suggests the energetic aurora is the cause of this, which generates and pushes heat from the aurora down towards the magnetic equator,” said lead author Emma Thomas, a PhD student in the University of Leicester School of Physics and Astronomy.

“A majority of exoplanets discovered so far fall in the sub-Neptune category, and hence are physically similar to Neptune and Uranus in size. This may also mean similar magnetic and atmospheric characteristics too. By analyzing Uranus’s aurora which directly connects to both the planet’s magnetic field and atmosphere, we can make predictions about the atmospheres and magnetic fields of these worlds and hence their suitability for life,” Thomas explained.

The results may also give scientists an insight into a rare phenomenon on Earth, in which the north and south pole switch hemisphere locations known as geomagnetic reversal.

“We don’t have many studies on this phenomena and hence do not know what effects this will have on systems that rely on Earth’s magnetic field such as satellites, communications and navigation. However, this process occurs every day at Uranus due to the unique misalignment of the rotational and magnetic axes. Continued study of Uranus’s aurora will provide data on what we can expect when Earth exhibits a future pole reversal and what that will mean for its magnetic field,” said Thomas.

“This paper is the culmination of 30 years of auroral study at Uranus, which has finally revealed the infrared aurora and begun a new age of aurora investigations at the planet. Our results will go on to broaden our knowledge of ice giant auroras and strengthen our understanding of planetary magnetic fields in our solar system, at exoplanets and even our own planet,” Thomas added.

ABOUT NIRSPEC

The Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSPEC) is a unique, cross-dispersed echelle spectrograph that captures spectra of objects over a large range of infrared wavelengths at high spectral resolution. Built at the UCLA Infrared Laboratory by a team led by Prof. Ian McLean, the instrument is used for radial velocity studies of cool stars, abundance measurements of stars and their environs, planetary science, and many other scientific programs. A second mode provides low spectral resolution but high sensitivity and is popular for studies of distant galaxies and very cool low-mass stars. NIRSPEC can also be used with Keck II’s adaptive optics (AO)system to combine the powers of the high spatial resolution of AO with the high spectral resolution of NIRSPEC. Support for this project was provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation.

ABOUT W. M. KECK OBSERVATORY

The W. M. Keck Observatory telescopes are among the most scientifically productive on Earth. The two 10-meter optical/infrared telescopes atop Maunakea on the Island of Hawaii feature a suite of advanced instruments including imagers, multi-object spectrographs, high-resolution spectrographs, integral-field spectrometers, and world-leading laser guide star adaptive optics systems. Some of the data presented herein were obtained at Keck Observatory, which is a private 501(c) 3 non-profit organization operated as a scientific partnership among the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The Observatory was made possible by the generous financial support of the W. M. Keck Foundation. The authors wish to recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that the summit of Maunakea has always had within the Native Hawaiian community. We are most fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct observations from this mountain.